[section]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 12]

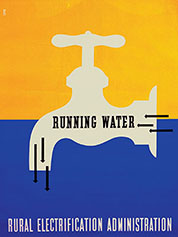

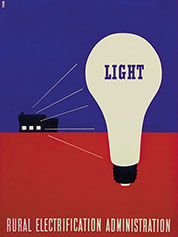

Simple elements defined the differences between the haves and the have-nots in America in the early days of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA): Running water. Radio. Light.

Such technological advances have always drawn the line between urban and rural. Today, it’s access to broadband, the so-called digital divide, that harkens back to life in the 1930s, when children in cities studied at home under electric lights while their rural counterparts labored beside kerosene lanterns.

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 12 center]

[image-caption title="Lester%20Beall,%20Light%201937%20Art%20%C2%A9%20Dumbarton%20Arts,%20LLC/Licensed%20by%20VAGA,%20New%20York,%20NY" description="%20" image="/remagazine/articles/PublishingImages/Original6_Beall-farm-v1_Page_3.jpg" width="280" /]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

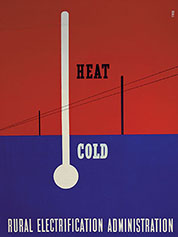

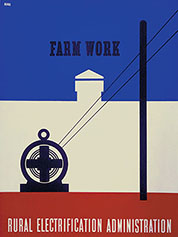

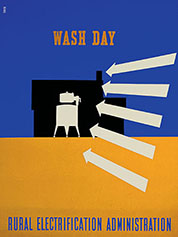

In 1936, the REA began a campaign to build public support for rural electrification. For the project’s art pieces, the agency turned to renowned Midwest graphic designer Lester Beall. His initial series of posters, six in all, identified amenities brought by electricity to American cities starting in the 1880s but that rural communities and farms still lacked.

“Wash Day” points to the time-saving promise of the first electric clothes washers. “Light” is a white electric lightbulb, a beacon of modern times, emanating from a small home. “Radio” shows a farmhouse illuminated by news, information, and entertainment. “Running Water” demonstrates easy access to the lifeblood of the farm. And in his images of “Farm Work” and “Heat/Cold,” the poles and wires of distribution systems are dark shadows: negative space to describe infrastructure that was, at the time, missing from the rural picture.

The posters were an instant success, winning critical acclaim and popular praise, even earning Beall the first single-artist show by a graphic designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1937.

It won’t surprise anyone who sees Beall’s work that, as a student at the University of Chicago, he switched majors from the sciences to the art history program. His succinct style earned broad critical enthusiasm and was described as a kind of visual engineering, heavy with purposeful fonts and blocks of color that divided his works with tension. His buildings and machinery don’t appear to be drawn at all; they look like they were hoisted and then carefully placed by an off-canvas crane.

But if he accepted the REA project for artistic reasons, Beall also bore in mind the powerful connection between public art and political activism. “Applied good taste is a mark of good citizenship,” he said. “Ugliness is a form of anarchy ... ugly cities, ugly advertising, ugly lives produce bad citizens.”

And in barns and sheds, on the walls of cafes and the vestibules of churches, at town halls and in the public spaces of daily life, advocates posted those plain-spoken statements in support of good citizenship. Beall set REA’s argument in unassailable terms: There are life enhancements that only electricity could provide.

Read another way, Beall’s work posed a list of demands: health and safety, economic prosperity, access to information, and admittance to the efficient, modern home.

[section]

[section-item]

[row]

[column 4]

[/column]

[column 4]

[/column]

[column 4]

[/column]

[/row]

[row]

[column 4]

[/column]

[column 4]

[/column]

[column 4]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

It’s easy to look back and ask the “what if?” question of Beall’s works: What if the REA hadn’t succeeded in making the case for rural electrification?

The fearful answer is that none of the crucial investments in modernizing homes and businesses across the plains, hills, and deserts of rural America would have happened. The nation’s breadbasket would have been substantially more spare, the rural population disconnected and even unprepared for the challenges faced by a country headed out of economic depression and into war.

Thankfully, those consequences never came to pass.

Today, the challenges of running water, radio, and light in rural areas have been replaced by the very real problems of underemployment, aging infrastructure, and a new type of lack of access. In particular, today’s rural communities thirst for things like broadband Internet, entrepreneurial business opportunities, distance learning, and telehealth.

Co-ops in these regions contend with difficulties as well, including deploying a modern electric grid that ensures physical- and cyber security; attracting and retaining a skilled next-generation workforce; building an engaged community of member-owners who understand the responsibilities of the cooperative model; and deploying costly technologies to meet renewable energy mandates and efficiency standards.

The “what if?” question of the moment is not so easy to ask: What if we don’t succeed in making the case to continue the electric cooperative model? What if we lose our connection to a new generation of policymakers, presidents, advocates, and member-owners entrusted with building on the hard work of electrification?

Those questions come at an opportune time for America’s electric cooperatives.

NRECA’s upcoming 75th anniversary is a chance to remind ourselves of the legacy of the electric cooperative program while also striding boldly into the future, together. The rich past of electric cooperatives is not yet too distant. The future is by no means far off. And Lester Beall’s words are especially relevant to us now: “We should envision ourselves as the inevitable architects of future revolutionary systems of communications.”

The simple language Beall used for his revolutionary communication in those first six posters for the REA are a useful starting point in a renewed national conversation. As electric cooperatives set their minds on the future, we can rely on similar phrases.

Think about a modern set of electric cooperative posters. What aspirations would they depict? What audiences would they address? Answering such questions may be the clearest way to cut through today’s politics and noise and set our new imperatives.

Electric cooperatives have never shied away from audacious goals. We won’t need any more words to articulate our ambitious vision today than Lester Beall did when his work shaped the national view of rural priorities so many years ago.