In its native range in the Siberian forests and Central Asian steppes, the emerald ash borer (EAB) leads a quiet life. But the metallic-green beetle arrived in North America some 15 or 20 years ago, riding crates and pallets aboard cargo ships docking in Detroit, and now it’s creating major—and costly—problems for vegetation managers throughout the Midwest.

[image-caption title="%20Emerald%20ash%20borer%20damage%20on%20a%20dead%20tree%20trunk.%20(Photo%20courtesy%20Getty%20Images)" description="%20" image="/remagazine/articles/PublishingImages/GettyImages-157602074_CMYK-600x398.jpg" /]

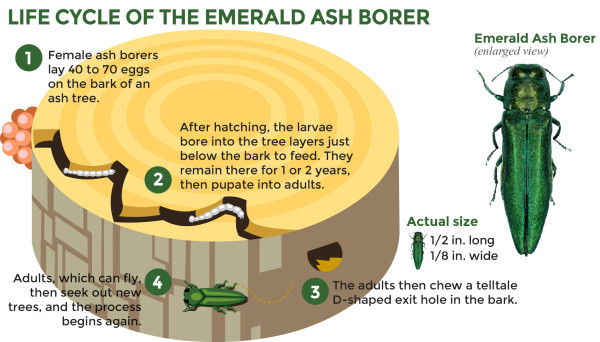

The adult beetle itself poses little threat, but it lays eggs in the bark of every species of ash found in in America. When the eggs hatch into larvae, these worm-like creatures bore into the tree to eat, destroying the tree’s vascular system for water and nutrients. In the late spring, the adult beetle emerges from a distinctive D-shaped hole to start the cycle again. Another sign of EAB infestation is the presence of voracious woodpeckers, who tear apart the bark of the tree to reach the larvae.

EABs have left millions of dead trees waiting to topple. While the ash borer has been found as far west as Denver, as far east as New Hampshire, and as far south as Louisiana and Georgia, it’s hit the Midwest the hardest by far.

And that puts Ted Harpe right in the middle of the ash EAB outbreak. Harpe is manager of vegetation management & locating services at Hendricks Power Cooperative in Avon, Ind., which serves about 30,000 meters west of Indianapolis, starting in the suburbs and shading into wooded, rural countryside.

“We just started noticing it last year, the trees not leafing out,” he says. “You’d go along and see all this beautiful greenery, and then bam, a dead tree. We’re going to be full blown this summer, three or four times worse than it was last year.”

Harpe’s partner in tree trimming and removal is Asplundh Tree Expert Co., a Pennsylvania consulting and contracting company that has worked with Hendricks Power for more than a decade. Robbie Adkins, the Asplundh regional manager whose territory includes Hendricks Power, is all too familiar with the co-op’s EAB problem.

“There are certain areas that basically are devastated,” Adkins says.

Asplundh has added crews and equipment to tackle the fast-growing problem, he says. In members’ backyards, along rights-of-way, and even deep in the woods, the company’s aim is to remove even potentially hazardous ash trees that threaten power lines.

“We’ve been cutting thousands of them down every year,” Adkins says. “We’re just trying to get them down safely before they all die. I’d rather get them when they’re green. They’re unpredictable and unsafe to climb once they’re dead or dying.”

The sheer number of trees that need to be taken out is one thing. But work-safety rules forbid climbing dead or dying trees, so they must be taken down in stages by trimmers in aerial lift trucks and tracked backyard lifts. Fortunately, using this equipment is safer and more efficient, helping to control the cost of so many removals.

“We’re going to spend half a million dollars, easy, this year just on ash-tree removal,” Harpe says. “For a rural electric like ours, that’s a lot of money. But our board’s been very gracious. They understand it, and they’re all in total agreement that we need to keep this pace up and try to stay ahead of it as much as possible.”

Homeowners aren’t always so gracious. Ash trees are pleasing, popular trees in rural and suburban landscapes, leading some homeowners to resist removal efforts.

“It’s one of the most perfect trees you can have in terms of landscaping,” Harpe says. “It’s pretty amazing that it’s this tree, of all the trees, that’s having this problem. I’ve had homeowners walk out and say, ‘My great-grandfather planted that tree back in the 1930s.’ I’ve had ladies cry when I tell them we have to take one down. It’s tough.”

The dead and dying ash trees are often 50 to 90 feet tall, Harpe adds, which means he and Asplundh’s crews must look well outside the right-of-way to find all the “hazard trees” that threaten co-op lines.

“There’s no safe-fall zone,” he says. “If you have a line with 1,500 homes on it, it behooves us to do something about that tree. We just think it’s worth the money to deal with it now, rather than pay dearly for it later.”

‘It Just Kind of Explodes’

[image-caption title="An%20emerald%20ash%20borer%20beetle.%20(Photo%20courtesy%20David%20Cappaert)" description="%20" image="/remagazine/articles/PublishingImages/david-cappaert-michigan-state-university-bugwood1-600x362.jpg" /]

Aaron Trezona, the shared system arborist for three co-ops in two states on the western banks of the Mississippi River, is facing the same problems with dead ash trees threatening his co-ops’ lines.

The trees started dying about six years ago in territory served by Allamakee-Clayton Electric Cooperative, a 10,000-meter co-op headquartered in Postville, Iowa. Then, the ash borer showed up at Tri-County Electric Cooperative, which serves 15,000 meters from Rushford, Minn. This spring, some ash trees failed to leaf out around Cresco, Iowa, where Hawkeye Rural Electric Cooperative serves about 7,000 meters.

“I’m very familiar with the emerald ash borer,” Trezona says with a frustrated sigh. He remembers first hearing about the deadly bug when it was found in a small patch of ash trees inside an interstate cloverleaf.

“I thought, that’s just a quarter-acre or so,” he remembers. “Now, only three years later, it’s about 300 square miles. It just kind of explodes on you.”

Trezona’s been working long and hard with his tree consultant, Davey Resource Group, to identify, mark, and record the dead and threatened trees in his three co-ops’ service territories.

“What we’re finding with the ash trees is they become very brittle very quickly, and they basically fall from the base,” says Jim Neeser, a Minnesota-based business developer for Davey Resource Group. “Most of the outages come from outside the right-of-way, so you’ve got to go outside the right-of-way.”

That’s certainly been the case for Trezona and his co-ops, where steep river bluffs and hills magnify the threat from already tall trees. “Trees more than a hundred feet off the line can still get us. It creates a real serious situation,” Trezona says.

When it came time to prepare a budget to fight the tree threat, he confronted that serious situation with an equally dire projection.

“I estimated we could have 54 members out of power daily over the next 10 years because of this ash borer problem if we did nothing to mitigate it,” he says. He needed that attention-getting figure for what came next. “In order to protect our 2,700 miles of line, we’re going to need an extra $1.6 million over the next 10 years. That’s about an additional 20 percent over our normal budget.”

In addition to the help with line patrol, ash tree identification, marking, and member contact he’s getting from Davey Resource Group, Trezona says the company is also assembling a comprehensive database. His trimming and cutting contractors use that database, but he hopes he’ll have reason soon to share it with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

“I don’t know if there’s ever going to be FEMA money available, but if there is, I want to make sure I’ve got all the documentation I need,” Trezona says, adding that the agency should be paying just as much attention to the emerald ash borer as he and his co-op counterparts are.

“I consider this to be a natural disaster,” he says.