[section]

[section-item]

[row]

[column 12]

[vimeo url="https%3A%2F%2Fvimeo.com%2F798385651%2F" /]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

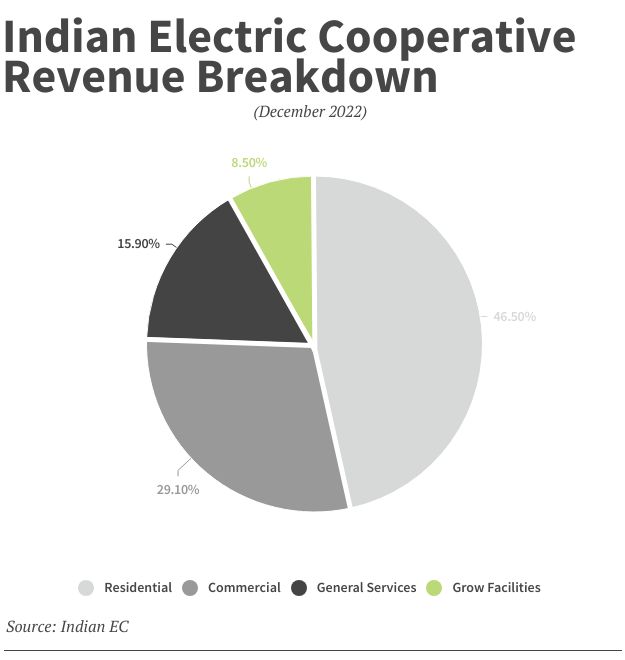

Indian Electric Cooperative has seen an explosion of nearly 200 cannabis grow houses in its service territory in the four years since Oklahoma legalized medical marijuana. The result has been a compelling tale of big rewards and unique challenges, with lessons for other co-ops as more and more states legalize and decriminalize the plant’s cultivation, sale and use.

[section separator="true"]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 11]

The benefits for Indian Electric include millions in new revenue and stable rates for its consumer-members because of the hefty boost in sales. But these electricity-intensive businesses have also brought unforeseen dilemmas for the co-op, such as how to communicate with growers from other countries and process thousands of dollars in cash payments each month.

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 12]

[image-caption title="(Left)%20Michael%20Mizelle%2C%20head%20gardener%20and%20manager%20of%20Pharma%20Flower%20in%20Oklahoma%2C%20with%20Jeff%20Pollard%2C%20Indian%20Electric%20Cooperative%E2%80%99s%20vice%20president%20of%20engineering." description="%20" image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2Findian-electric-grow-houses-cover.JPG" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2Findian-electric-grow-houses-cover.JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

The 20,000-member co-op, located just outside Tulsa, and other co-ops serving grow houses throughout the country are offering their experience and advice as these operations expand in rural areas.

“It’s coming to a lot of places, and co-ops need to be prepared,” says Allison Hamilton, NRECA’s director of markets and rates.

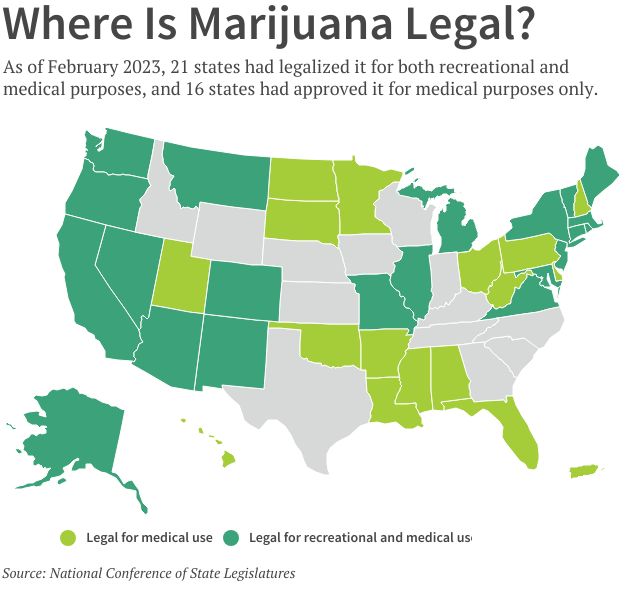

The number of states with some degree of legalized marijuana has risen with each election cycle. As of February 2023, 21 states had legalized it for both recreational and medical purposes, and 16 states had approved it for medical purposes only, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

What happens after a state legalizes marijuana varies widely depending on state and local regulation of the industry. Co-ops that serve growers say it’s hard to generalize about what to expect.

[section separator="true"]

[section-item 4]

[row]

[column 12]

Inside Indian Electric Cooperative’s service area, where permitting requirements have been minimal, the situation can best be described as “the wild, wild West for marijuana,” says Jeff Pollard, the co-op’s vice president of engineering.

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[section-item 8]

[row]

[column 12]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

Pollard regularly uses Google Translate to communicate with growers who have flooded in from other countries for the cheap land.

Co-op employees are confronted with backpacks and grocery tote bags full of cash from growers paying power bills. Marijuana is still illegal at the federal level, which means most growers have difficulty accessing the federally regulated banking system.

“We actually have some growers that will come in after-hours and feed the kiosk until it won’t take any more money,” Pollard says. “One guy would come out and sit in a lawn chair and feed the kiosk.”

Banks are reluctant to open accounts for marijuana growers in states where marijuana has been legalized, says Nick Pascale, NRECA’s deputy general counsel.

[image-caption title="A%20dispensary%20operates%20from%20a%20nondescript%20building%20on%20Main%20Street%20in%20Fairfax%2C%20Oklahoma%2C%20across%20the%20street%20from%20Indian%20Electric%20Cooperative%20headquarters.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" description="%20" image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(21).JPG" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(21).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

“As a result, it creates safety, operational and accounting issues for co-ops,” he says. “Also, in some circumstances, the co-op may have a legal obligation to report cash payments of $10,000 or more to the Internal Revenue Service, and that’s just one example of the challenges created due to the inconsistency between federal and state law regarding the marijuana industry.”

Crew safety is also an issue, Pollard says.

IEC’s lineworkers have to travel in pairs as they confront, in some cases, massive sheet-metal fences, armed guards and dogs when they make service calls. Some of the growers from other countries have even offered bribes to co-op crews to try to get them to expedite construction projects, Pollard says.

“It may be standard business practice in other countries, but it’s not the way it is here,” he says. “We have to remind them that we’re a cooperative, and we have to treat everybody the same.”

'Great loads'

Despite some unique challenges, grow houses have benefited the co-op’s members by boosting sales and keeping rates down, Pollard says.

“As a member of a cooperative, I see it as a good thing because it keeps my rates stable,” he says.

[section separator="true"]

[section-item 4]

[row]

[column 11]

Grow houses have also helped keep electric rates from rising at co-ops in Montana, where both medical and recreational marijuana are legal.

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[section-item 8]

[row]

[column 12]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

Yellowstone Valley Electric Cooperative in Huntley, Montana, served just a few grow houses when the state restricted marijuana use to medical purposes. Now, with recreational use legalized for adults, 15 grow houses are operating in its territory, says CEO Brandon Wittman.

“It hasn’t really been overwhelming for us,” he says. “These are great loads.

“We have some commercial members that are heavy users for eight to 10 hours a day. The difference with these grow houses is that they are almost 24/7 loads. If you install a 500-kilovolt transformer, they’re going to use that thing around the clock. That’s equivalent to powering 40-plus homes.”

Unlike Oklahoma, a majority of the growers in YVEC’s territory are “local folks,” Wittman says.

“I think that has a lot to do with land prices,” he says. “It’s a super high real estate market right now. Our growth is off the charts. We’re seeing some people coming in from the Pacific Northwest, from Washington, Oregon and California, where land is still more expensive.”

Scott Peters, CEO of

Columbia Rural Electric Association in Walla Walla, Washington, says strict county regulations have limited the number of grow houses in his co-op’s territory to a handful.

[image-carousels slides-to-show="1" infinite="true"]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(60).JPG" title="Indoor%20agriculture%20operations%20are%20energy%20intensive%2C%20with%20a%20near%20round-the-clock%20need%20for%20specialized%20lighting%2C%20ventilation%20and%20air%20conditioning.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(60).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(14).JPG" title="After%20about%20three%20weeks%2C%20clones%E2%80%94small%20cuttings%20taken%20from%20vegetating%20mother%20plants%E2%80%94have%20grown%20to%20about%208%20inches%20tall%20and%20are%20ready%20to%20be%20planted%20in%20soil.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(14).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(41).JPG" title="Marijuana%20plants%20in%20the%20vegetative%20phase%20like%20these%20are%20placed%20under%20specialized%20grow%20lights.%20At%20this%20grow%20house%20in%20Fairfax%2C%20Oklahoma%2C%20those%20lights%20stay%20on%20for%2018%20hours%20a%20day.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(41).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(9).JPG" title="Fans%20run%20nearly%20constantly%20to%20circulate%20fresh%20air%20and%20control%20temperature%20and%20moisture.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(9).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(50).JPG" title="Cannabis%20is%20a%20tropical%20plant%2C%20and%20growers%20generally%20keep%20the%20temperature%20between%2070%20and%2085%20degrees%20in%20the%20grow%20rooms.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(50).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(44).JPG" title="An%20array%20of%20lights%2C%20fans%20and%20drip%20systems%20maintain%20the%20ideal%20climate%20for%20the%20cannabis%20plant%20to%20grow.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(44).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[image-carousel image="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(19).JPG" title="Grow%20houses%20accounted%20for%20almost%209%25%20of%20Indian%20Electric%20Cooperative's%20revenue%20in%20December%202022.%20(Photo%20by%20Denny%20Gainer)" link="%2Fremagazine%2Farticles%2FPublishingImages%2FIndian%20Electric%20Grow%20Houses%20(19).JPG" linking="lightbox" /]

[/image-carousels]

“We just treat them like any other commercial grower,” says Peters, who has far more wineries on his co-op’s lines than marijuana growers. “They’re local folks who are all known commodities. If we thought they were fly-by-night operations, then we might have done something different. But they’re not.”

Peters says he’s much more concerned about cryptocurrency miners, who can quickly strain an electrical system and often leave in the middle of the night to move somewhere with cheaper power.

“That kind of a situation worries me a lot more than farmers, whatever they’re farming,” he says.

Both Peters and Wittman describe their local grow house operators as good co-op members.

“They pay their bills, and they pay them on time,” Wittman says.

Co-op power

Growers say electricity is the lifeblood of their operations, and they can’t afford to lose power or the carefully controlled growth cycle of their marijuana plants will be disrupted, threatening their fragile crop.

“We’ve got to have reliable power. An outage is our biggest fear,” says Kevin Hance, a YVEC member and owner of 312 Cannabis in Montana, which includes two grow houses and three retail dispensaries. “If the lights go out and don’t come back on quickly, the plants start to change. In the vegetative cycle, you want 24 hours of light so the plant knows it’s just supposed to grow and not supposed to flower yet.”

Hance, whose business spends thousands each month on electricity, says he blew out a transformer at one of his grow locations and immediately called the co-op for help.

[section]

[section-item]

[row]

[column 12]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

“They could tell it had gone out, and they dispatched someone to fix it even before I called,” he says. “They got it repaired real quick.”

Freezing Montana winters could be “devastating” if an outage knocked out the heating system, says Kyle Knight, a YVEC member and owner of Frosteez Cannabis Co., which produces about 1,000 pounds of cannabis a year.

“Cannabis is a tropical plant, and it really is temperamental,” Knight says. “We keep it at 70 to 85 degrees in the grow rooms. If anything goes wrong with the power, it would be an almost total loss.

“The good thing is we’ve never experienced any extended outages with the co-op. There was just one short blip when someone ran into a power pole, and the co-op was on it right away.”

'There isn't a handbook'

Paul Erickson, CEO of 13,000-member

Sangre de Cristo Electric Association in Buena Vista, Colorado, says the three legal grow houses operated by local residents in his co-op’s territory are good members and “very professional.” The problem, he says, is the dozen or so illegal operations.

Colorado was one of the first states in the nation to legalize marijuana, but that hasn’t shut down the illegal operators as hoped, Erickson says. Instead, a 2012 amendment to the state constitution making it legal for residents to grow up to six marijuana plants in their homes brought in a wave of illegal growers, he says.

“Opponents argued that there would be more illegal grows hidden in plain sight, and they were right,” Erickson says. “This is a mountainous area, and people come and hide out here. The difference between the legal grow and the illegal grow is that the legal grow is still going to be here next month. The illegal operations come and go, after some of them run up large electric bills.”

The co-op doesn’t have the resources or authority to try to figure out who is and isn’t operating legally, he says. But, to protect its other members from having to pick up the cost for a questionable operation, the co-op requires a grower who is suddenly using a lot of power to pay an industrial rate with an upfront deposit for at least three months of service, Erickson says.

“As time goes by, if I’m noticing they’re using six to 12 months’ worth of power in a single month, I’ll tell them, ‘You need to get in here now. You’re not a residential account. You have to give us a minimum of at least three months of payments in advance or we’re shutting you off.’”

[section separator="true"]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 10]

The operation also will be required to pay upfront for any upgrades needed to meet their demand for electricity, Erickson says.

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[section-item 6]

[row]

[column 12]

[/column]

[/row]

[/section-item]

[/section]

“They’re usually desperate and are willing to pay anything to get it done,” he says. “We don’t like these scary people demanding this stuff of us. … It’s real tricky. There isn’t a handbook for dealing with these situations.”

Co-ops that serve grow houses advise their colleagues to have a strong policy about how to handle requests for service upgrades, regardless of what type of business is seeking the construction.

“Co-ops really need to look at their line-extension policies,” Erickson says. “You’re not discriminating against marijuana growers or anyone else if you say, ‘This business needs a massive service upgrade; who is going to pay for that?’ Our policy is that you’re going to pay for all of that before we energize, so we need those funds upfront and that’s it.”

As more and more grow houses move into rural communities, the response from co-ops will be varied, Pascale says.

“The political, operational and economic circumstances at each co-op are different,” he says. “There are efforts to change federal law, and state laws may differ, which creates a complex universe of considerations. So it’s no surprise that co-ops are taking different approaches to marijuana growers in their service territories. Some are more accommodating, some are not.”

At Indian Electric Cooperative, which has experienced both the opportunities and challenges of serving these new commercial members, Pollard advises his colleagues not to panic.

“There’s always going to be something new coming down the pike, whether it’s grow houses, EVs, cryptocurrency miners or something else,” he says. “It’s just a matter of being innovative and trying to look forward to find solutions.”